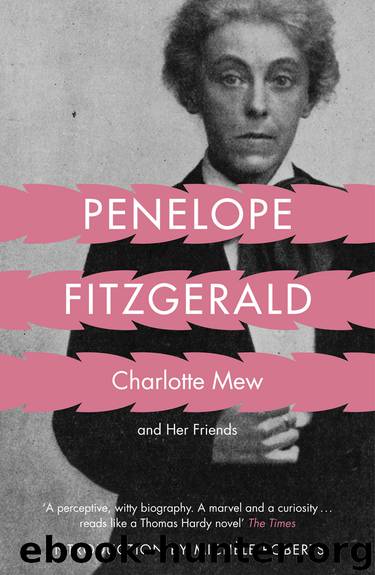

Charlotte Mew by Penelope Fitzgerald

Author:Penelope Fitzgerald [Penelope Fitzgerald]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Published: 2014-03-17T16:00:00+00:00

Letter from Charlotte Mew to Mrs Dawson Scott, 24 June 1917. ‘People are only “disappointing” when one makes a wrong diagnosis …’

‘Blindest of all the things that I have cared for very much In the whole gay, unbearable, amazing show.’ Was it necessary for May Sinclair to tell so many people about it – Charlotte had no way of knowing how many? ‘I don’t think there’s anything quite so deadly as “giving people away”,’ she had told Mrs Dawson Scott a few months earlier, ‘but it never seems they are given away to me – because I think I see beyond their weakness and their poses – “we are all stricken men” one way or another – and the only thing I have no mercy for is hardness and deadness.’ She had made herself ‘dam ridiculous’, in her own phrase, and more so than she had ever dreaded. Perhaps she felt that Mrs Sappho, to whom she owed so much, might have made more allowance for her. Something was broken between them that could never be mended. Three years later, when Sappho had founded the first of her writers’ organizations, the Tomorrow Club, she was disappointed because Charlotte refused formally (though not very politely) to come and read to them, in the old way. ‘People are only “disappointing”’, Charlotte wrote in this letter, ‘when one makes a wrong diagnosis.’

In August 1914 the outbreak of war separated them all. Dr Scott joined the RAMC, Mrs Dawson Scott set to work on plans for a Women’s Defence League, Edith Oliver began training in Queen Alexandra’s Nursing Yeomanry, Evelyn Millard, who had been appearing as Cho-Cho San in Madam Butterfly, switched to a patriotic Queen Elizabeth in Drake at the Coliseum. Charlotte, who was home-bound, and had what was then called ‘no men to give’, extended her visiting to the volunteers’ wives who had for several months no idea when and where to collect their allowance of three shillings a week. Very soon, too, there were the widows of some of the first 32,000 casualties.

But in the almost unbelievable early anxiety to be in the thick of ‘the show’ May Sinclair seemed to be well ahead of the field. From September to October she was in Belgium with an ambulance team sent out by the Medico-Psychological Unit and working with the Belgian Red Cross. The commandant was Dr Hector Munro, the clinic’s consultant. May acted as secretary and contributed a good deal of the funds. But she was used to organizing things in her own way, and perhaps showed this a little too plainly. The first weeks of inactivity, before the refugees from the German advance arrived, were the worst. ‘I began to feel like a large and useless parcel which the commandant had brought with him in sheer absence of mind.’ A few days later, according to her Journal of Impressions of Belgium, she was ‘coldly and quietly angry’ with the commandant. ‘I don’t quite know what I said to him, but I think I said he ought to be ashamed of himself.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19053)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14081)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12035)

Becoming by Michelle Obama(10032)

Educated by Tara Westover(8060)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7892)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5102)

Hitman by Howie Carr(5101)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4974)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4931)

On the Front Line with the Women Who Fight Back by Stacey Dooley(4875)

Year of Yes by Shonda Rhimes(4763)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4278)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4117)

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3893)

Patti Smith by Just Kids(3782)